A concise guide for policymakers, academics, civil society organisations, and peace practitioners.

1. “How does the Parity Accord relate to the Good Friday Agreement — and how should it be evaluated?”

The Good Friday/Belfast Agreement was designed as a peace settlement to end conflict and establish consent. It deliberately left the final constitutional form unresolved. In doing so, it reframed Ireland as a community of people rather than a question of territory.

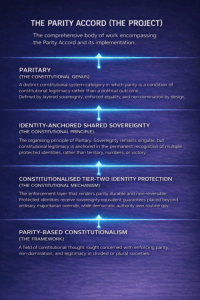

The Parity Accord builds upon that shift by developing the constitutional framework required to govern a shared society made possible by consent under the Agreement.

It addresses a structural problem left unresolved by the Agreement: how two enduring peoples can inhabit a single political space when, under majoritarian or territorial systems, constitutional recognition of one has repeatedly been experienced as the erasure of the other.

For this reason, the Accord must be assessed not as a discrete policy proposal but as a complete constitutional system designed to resolve that problem structurally rather than rhetorically. Proper evaluation therefore requires consideration of its four interlocking components:

-

Introduction: Evolving the Good Friday Agreement

-

The New Constitutional System

-

The Policy Paper – Sixteen Pillars

-

Strategic Defence of the Parity Accord

Together, these texts enable legal, institutional, and comparative assessment of how parity, non-domination, and layered sovereignty are embedded across the framework.

2. “What makes the Parity Accord structurally distinct from existing constitutional models?”

The Parity Accord is not a variation of existing constitutional forms. It introduces a distinct constitutional category in which a governing principle—Identity-Anchored Shared Sovereignty—is rendered durable through constitutionalised Tier-Two identity protection and operationalised through the structural mechanisms set out below:

Constitutionalised Tier-Two Identity Protection

Establishes sovereignty-equivalent guarantees of permanence and non-domination for protected identities, placing them beyond majoritarian override while remaining within a single sovereign state.

Identity-Anchored Shared Sovereignty

Structures a single Tier-One state sovereignty alongside a Tier-Two constitutional identity layer, enabling the shared exercise of authority without territorial redefinition.

Neutral Administrative Centre

Creates a constitutionally non-aligned locus of governance, removing victory–defeat dynamics from contested institutions through non-territorial constitutional authority.

Overlapping, Reparative Representation

Restores representational continuity across communities without altering borders, addressing constitutional ruptures caused by partition, separation, or exclusion while avoiding duplication or fragmentation.

Unified Three-Strand Architecture

Integrates internal governance, cross-community cooperation, and external relations into a single enforceable constitutional structure, unifying relationships that are otherwise fragmented across political domains.

Structural Stability (Anti-Fragility)

Embeds stability directly within the constitutional architecture, enabling the system to absorb political pressure through review and recalibration rather than collapse, independent of goodwill or elite cooperation.

Taken together, these elements constitute a framework irreducible to federalism, consociationalism, autonomy, or unitary redesign. They define Paritary as a constitutional model grounded in an established European governance tradition of paritary arrangements (derived from the French “paritaire” )—systems of joint authority and equal representation widely used in labour law, social partnership, and administrative governance.

The Parity Accord constitutionalises this paritary logic through the shared exercise of sovereignty and authority between protected identities as a structural condition of legitimacy, rather than as a numerical allocation mechanism. Its purpose is to stabilise identity-based and ideological conflict within a single constitutional order.

3. “How is the Parity Accord structured as a constitutional model?”

The Parity Accord is constructed as a layered constitutional framework distinguishing agreement, genus, system, and principle while integrating them into a single coherent architecture.

Rather than inventing governance anew, the model selects, integrates, and strengthens resilient elements of existing constitutional systems while removing known failure points in divided societies.

It deliberately distinguishes four interlocking layers, each performing a distinct constitutional function:

Each layer performs a different role:

one secures consent and legitimacy;

-

one defines constitutional form;

-

one governs authority and institutions;

-

one anchors the system in enforceable parity.