Prepared for Expert Review and Policymaker Consideration

Executive Summary

This document outlines a comprehensive constitutional framework for an agreed system of shared governance, designed to ensure stable administration, legal continuity, and balanced representation across all regions. Building on the principles established in the Good Friday Agreement, the framework translates those commitments into a modern, operational structure that prevents majoritarian control, upholds parity in decision-making, and secures economic and administrative stability during and after transition.

The Good Friday Agreement (1998) — approved by referendum North and South — authorised constitutional change by consent. The Parity Accord builds on that democratic foundation, providing the constitutional structure the Agreement deliberately left open. It does not replace consent — it operationalises it, completing the Agreement’s unfinished constitutional logic. Where Article 1(vi) recognises identity parity in principle, the Parity Accord gives that parity durable constitutional form, ensuring it cannot be overridden by demographics, territorial change, or majoritarian politics.

The model defines the core institutions, decision-making procedures, and distribution of powers required to operate a coherent constitutional order. It sets out clear distinctions between national, regional, and shared competencies, supported by mechanisms that guarantee cross-community leadership, legislative balance, and independent constitutional oversight. These arrangements ensure that authority is exercised in a manner that is structured, transparent, and inclusive.

A strengthened system of intergovernmental cooperation provides a permanent forum for coordination between the island’s political bodies, ensuring continuity in areas such as rights, mobility, trade, and public services. The framework embeds legal protections to ensure that no individual loses access to entitlements, services, or safeguards as constitutional arrangements evolve. A phased implementation process establishes a clear pathway for institutional development, administrative alignment, and policy harmonisation, ensuring stability throughout transition.

This document sets out the institutional architecture necessary for a stable and inclusive constitutional order: the composition and function of national bodies, the legislative process, judicial arrangements, oversight mechanisms, intergovernmental links, economic coordination, and the transition procedures required to support them. It is intended as a technical and operational guide for implementing balanced, lawful governance within a shared constitutional framework.

Constitutional Legitimacy and Decision-Making Balance

To ensure that governance cannot be dominated by any single community, the system operates through a model of dual-source constitutional legitimacy. This approach requires that major constitutional and institutional decisions draw support from both primary identity traditions, preventing unilateral control while avoiding the rigid veto structures that weaken other power-sharing models.

Instead of granting permanent blocking powers, the framework establishes parity-based decision pathways that require cross-community assent, structured negotiation, and independent constitutional oversight. These mechanisms ensure that legitimacy is distributed rather than concentrated, enabling balance without paralysis and protection without domination.

This structure addresses the vulnerabilities observed in traditional majority-rule and consociational systems by embedding shared authority, non-domination guarantees, and stable decision-making procedures within the constitutional order itself.

Core Objectives:

-

Political Stability – Embedding structured power-sharing mechanisms that prevent majoritarian control and ensure inclusive governance across all parts of the island.

-

Balanced Representation – Maintaining regional legislative participation within a cohesive constitutional framework that supports co-operative decision-making.

-

Institutional Neutrality – Establishing a central administrative framework designed to prevent regional or identity-based dominance and ensure equal access to national institutions.

-

Rights and Identity Protections – Embedding legal and cultural safeguards that uphold existing rights and support cooperation across the island. Within this model, Irish and British identities are constitutionally recognised and permanently protected, while the Northern Irish identity is secured as a recognised civic identity, guaranteed equal status, dignity, and protection within shared institutions. All identity protections are upheld through sovereignty-equivalent constitutional guarantees, independent of future political change.

-

Economic Continuity – Securing trade stability, regulatory clarity, and access to existing markets to ensure long-term economic confidence during and after transition.

Comparative Principles Informing This Architecture

Ireland’s circumstances are unique, but not without broader lessons.

Across the world, diverse societies have developed ways to balance identity, prevent dominance, and reinforce shared governance.

This framework draws from those principles conceptually, not to replicate any foreign model, but to identify what consistently works in plural, post-conflict, or multi-identity contexts. The insights applied here are adaptive rather than derivative, and rooted firmly in the Good Friday Agreement.

Three Comparative Principles Are Relevant:

1. Subsidiarity and Localised Authority

Stable multi-community systems ensure that decisions are taken at the most local effective level, preventing domination and strengthening trust in shared institutions.

2. Rotational and Non-Concentrated Executive Power

Models such as Switzerland demonstrate that circulating leadership, rather than a fixed executive, reduces symbolic imbalance and strengthens political neutrality.

3. Protected Identities within Shared Structures

Plural societies maintain stability when cultural autonomy, language rights, and parallel identities are protected within a common constitutional framework, ensuring belonging without assimilation.

Why These Principles Matter for Ireland

Together, these lessons reinforce several core requirements:

-

shared authority rather than majoritarian rule

-

constitutional protection for dual and parallel identities

-

institutions that guarantee balance, not victory

-

frameworks preventing any community from being overruled

-

structures where symbols, culture, and belonging are safeguarded

These principles align with — and strengthen — the foundations of the Good Friday Agreement.

They support an architecture that is distinctively Irish, grounded in parity rather than precedent.

Positioning These Principles Within an Irish Framework

This constitutional model is not modelled on any external state.

Instead, it evolves the Good Friday Agreement’s three-strand logic into a single coherent system:

-

Strand One: Democratic Institutions in Northern Ireland

-

Strand Two: North–South Institutions

-

Strand Three: British–Irish Institutions

Each is integrated within a framework defined by consent, balance, and no dominance.

Constitutionalised Identity and Sovereignty-Equivalent Guarantees

Constitutionalised Identity and Sovereignty-Equivalent Guarantees –

Within this framework, Irish and British national identities, alongside the Northern Irish civic identity, are formally constitutionalised and protected by sovereignty-equivalent guarantees.

These protections ensure that identity remains a permanent individual authority, unaffected by political institutions, administrative reform, or future constitutional change.

Identity is not granted by the state and cannot be withdrawn by the state.

It is safeguarded above political structures, ensuring that culture, belonging, and self-definition remain secure as governance evolves.

Clarifying How Identity Functions Within the Constitutional Model

To avoid the historical failures of systems that require the state to define, verify, or police identity, this framework embeds identity autonomy as a constitutional principle.

Identity affiliation is:

-

voluntary,

-

self-declared,

-

non-exclusive, and

-

capable of evolving over time.

Individuals may align with one identity, with both, or designate themselves as constitutionally neutral.

Under this model, identity protections do not create rigid categories or exclusion. Their purpose is to provide constitutional non-domination, ensuring that no community can be absorbed, marginalised, or reduced in authority, regardless of demographic or political change.

Transition to the Next Section

Having established the principles of balanced, non-dominant governance, the next step is to examine how these foundations translate into practical, shared institutions.

The following section begins this process by re-evaluating the legacy structures of the Good Friday Agreement and presenting their evolution into a modern, island-wide constitutional architecture:

1. Proposal: Reviving Shared Institutions — From the Council of Ireland to a Modern Governance Architecture.

1. Proposal: Reviving Shared Institutions — From the Council of Ireland to a Modern Governance Architecture

The Parity Accord builds directly on the Good Friday Agreement’s principle of consent, ensuring that any constitutional change must be lawful, democratic, and inclusive.

This section outlines how earlier institutional concepts — first developed in 1920, revisited in 1973, reaffirmed in 1985, and operationalised in 1998 — provide the structural foundation for a modern system capable of managing shared governance today.

Historical Basis for Shared Institutions

This proposal modernises key elements of:

-

the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, which first envisioned parallel legislatures with a shared coordinating body

-

the 1973 Sunningdale model, which proposed a revised Council of Ireland with executive functions

-

the 1984 New Ireland Forum, which emphasised structured cooperation

-

the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, which formalised intergovernmental mechanisms

-

the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which embedded power-sharing, consent, and North–South cooperation in treaty form

These precedents demonstrate a century-long, bipartisan recognition that some form of shared institutional architecture is necessary to manage relationships across the island.

A Structural Reality Acknowledged Since 1920

While the New Constitutional System does not rely on any political doctrine, it reflects the long-established reality of two distinct political and cultural communities on the island — a condition recognised in every major constitutional document since 1920. This framework does not endorse any ideological interpretation of that duality. Rather, it acknowledges the constitutional fact — affirmed repeatedly across the 1920 Act, Sunningdale, the Anglo-Irish Agreement, and the Good Friday Agreement — that governance on the island must be structured so that neither community is absorbed, neither dominated, and neither placed in a subordinate position.

The model accommodates this historical duality through balanced institutions, without implying territorial separation or providing ideological justification for past arrangements. This proposal builds on that structural duality to develop modern mechanisms of coordination, without implying territorial division or ideological endorsement.

Key Structural Elements:

To build on that continuity, this proposal begins with:

-

Two legislatures (Stormont and Leinster House) operating within a collaborative framework

-

A modernised Council of Ireland as a joint coordinating body for policy, services, and cross-border matters

-

Structured channels of cooperation between institutions, supported by oversight mechanisms and clearly defined competencies

These elements provide administrative stability, procedural clarity, and predictable coordination without altering existing democratic mandates.

Purpose of Reviving Shared Institutions

The aim is to create operational continuity while expanding institutional capacity for cooperation.

This ensures:

-

no disruption of governance

-

clear lines of authority

-

predictable mechanisms for joint decision-making

-

structured engagement between jurisdictions

This stage establishes the institutional bridge required for the later development of more integrated governance structures.

Preparing the Ground for Constitutional Architecture

By starting with existing institutions and proven mechanisms, the system evolves through:

-

legal continuity,

-

operational stability, and

-

incremental structural refinement,

Rather than abrupt redesign.

This prepares the groundwork for the next phase, where shared governance can be expanded, competencies clarified, and structural balance strengthened in a way consistent with democratic consent and operational practicality.

As these foundational structures take shape, a further question arises: what governance model can ensure that shared authority remains balanced, impartial, and resistant to domination?

To answer this, the system must draw from international examples where diverse communities govern together, where no tradition can dominate, and where leadership circulates rather than concentrates.

These requirements form the natural basis for the next section:

2. Proposal: A Swiss-Inspired Governance Framework for Ireland.

2. Proposal: A Swiss-Inspired Governance Framework for Ireland

This proposal draws from key elements of the Swiss governance model, which has demonstrated long-term stability in a country characterised by multiple identities, linguistic diversity, and regional autonomy.

The purpose is not replication, but the adaptation of principles that support balanced governance in societies where no single group can, or should, dominate.

Switzerland shows how neutral decision-making, rotational leadership, and shared executive responsibility can sustain stability across diverse communities. These principles provide an effective reference point for designing structures that ensure parity, predictability, and institutional balance on this island.

Key Principles Adapted from the Swiss Model

1. Rotational Leadership

Switzerland’s Federal Council operates through annual rotation of the presidency, preventing long-term concentration of authority.

Applied in an Irish context, this principle provides:

-

shared leadership among British-identifying and Irish-identifying representatives, with explicit constitutional recognition of Northern Irish civic identity

-

a structure where no tradition retains permanent executive dominance

-

a predictable and lawful mechanism for circulating authority

This approach ensures that leadership is symbolically inclusive and constitutionally stable.

2. Collective Executive Responsibility

In Switzerland, executive authority is held by a multi-member council, not a single head of government.

This model demonstrates the value of:

-

shared decision-making

-

multi-party participation

-

institutional continuity even during political disagreements

For Ireland, this principle supports the creation of an executive structure that reflects multiple identities and operates through consensus-based procedures.

3. Balanced Regional Autonomy

Swiss cantons retain significant autonomy, while participating in shared national structures.

The lesson in an Irish context is the value of:

-

preserving the self-governing authority of Northern and Southern institutions

-

embedding cooperation through structured coordination, not centralised dominance

-

ensuring both regions maintain political continuity while contributing to a broader constitutional framework

This approach respects existing democratic mandates while enabling integrated governance where required.

4. Institutional Neutrality

Neutrality in the Swiss system does not mean the absence of institutions — it means the institutions themselves operate in a non-dominant, impartial manner.

This principle supports the development of:

-

a neutral administrative centre for shared governance

-

institutions designed to operate above regional or cultural alignment

-

mechanisms that ensure neither tradition can claim ownership of central authority

This concept lays the foundation for identifying an equidistant governance hub appropriate for the island’s constitutional design.

Why Swiss Principles Provide a Suitable Foundation

These principles offer a coherent framework for addressing core governance challenges on the island:

-

rotational leadership prevents executive imbalance

-

shared decision-making strengthens legitimacy across communities

-

regional autonomy respects existing political realities

-

institutional neutrality provides a foundation for shared authority

-

collective governance reduces the risk of political standoffs

Together, they shape a system where governance is steady, impartial, and structured around balance rather than dominance.

The application of these principles naturally leads to the question of where shared governance should be anchored.

A neutral system requires a neutral administrative centre — one neither aligned with North nor South, and one capable of hosting shared institutions without cultural or political claim.

This provides the structural basis for the next section:

3. Proposal: Meath as the Administrative Province.

3. Proposal: Meath as an Administrative Province

The next phase of the constitutional design introduces the concept of an Administrative Province — a neutral governance space located at the geographical centre of the island, designed to host shared administrative functions and operate above regional or identity alignment. This phase consolidates the structural foundations required for balanced governance, ensuring that the administrative core of the system is neither Northern nor Southern, and cannot be claimed by either tradition.

Reinstating Meath — historically Midhe, the Fifth Province — provides a constitutional solution grounded in geography, heritage, and structural neutrality. Unlike the contemporary four-province framework aligned with regional identities and modern political borders, the Fifth Province belongs to neither community’s modern narrative. Its restoration constitutes a genuine geographic restructuring of the island, not an expansion of existing state boundaries.

This distinction is critical:

It demonstrates that the emerging constitutional framework is not a 32-county unitary model, but the creation of an entirely new constitutional configuration — one shaped around a central province rather than the absorption of one region into another.

For Unionists, this provides a foundational reassurance that the new structure is not the “old Republic enlarged,” but a rebalanced Ireland with a newly defined centre, designed from the ground up.

Historical and Cultural Foundations of Belonging

Meath’s unique heritage landscape ensures that the Administrative Province becomes a shared constitutional home, rooted in the historical belonging of both traditions:

-

At Uisneach and Tara, the Gaelic and Nationalist traditions locate their ancient cultural and political origins, forming a natural source of belonging for communities aligned with the Irish nation-building narrative.

-

Along the River Boyne, the Unionist and Protestant tradition finds its central historical touchstone, grounding identity and historical memory in the very landscape of the province.

-

At the Hill of Slane, the origins of Irish Christianity link both Catholic and Protestant traditions through a shared spiritual narrative.

Taken together, these sites form a territory where each tradition recognises a piece of its own story, ensuring that the Administrative Province is not a concession to one identity, but a shared territorial middle-ground.

Eliminating the North–South Binary

Designating Meath as a new Administrative Province creates the first real alternative to the structural binary that has shaped the island since partition. Instead of authority flowing from Dublin vs. Belfast, administrative governance is anchored in a neutral central province, signalling that:

-

the future constitutional order is not North vs. South,

-

sovereignty does not flow from the competing capitals, and

-

no tradition is asked to accept the authority of the other’s symbolic centre.

This shift — from a dual-centred island to a re-centred island — dissolves the political logic of partition at its structural root.

Purpose of the Administrative Province

Establishing Meath as the Administrative Province ensures:

-

a neutral constitutional anchor,

-

a non-dominant administrative centre,

-

a territorial structure that neither tradition owns,

-

a new geography that prevents the reassertion of either legacy state’s dominance.

This prevents the appearance or reality of absorption, and frames shared governance within a territory not historically or politically aligned with either jurisdiction.

A Foundation for the Next Stage

With the Administrative Province established, the system is now prepared for the next step: identifying the specific civic location within this province that can host the operational functions of shared governance.

The question now becomes: which centre within the Administrative Province can provide neutrality, accessibility, and symbolic balance, while also possessing the capacity to serve as the civic heart of the new constitutional structure?

The answer lies in identifying a location that is geographically central, historically credible, and civically equipped to host all-island administrative functions without implying dominance.

This leads directly to the next section:

4. Proposal: Athlone as the Civic Centre of the Administrative Province.

4. Proposal: Athlone as the Civic Centre of the Administrative Province

Having established Meath as the Administrative Province, the next step is identifying the specific civic location capable of hosting shared operational functions in a manner that is structurally neutral, geographically balanced, and free from the historical symbolism of either Dublin or Belfast. Athlone emerges as the most suitable location for this role due to its geographic centrality, infrastructural capacity, and longstanding recognition as a natural meeting point between Ireland’s regions.

Historical Recognition of Athlone as a Central Hub

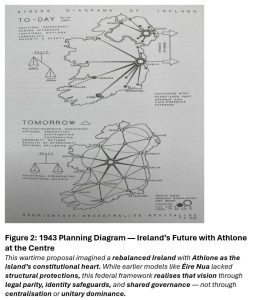

Athlone’s central position has long been acknowledged in Irish planning history. During the 1940s, national planners identified Athlone as a potential constitutional and economic midpoint capable of rebalancing the island’s internal structures.

Earlier decentralisation concepts such as Éire Nua also recognised the need to move beyond single-capital dominance. However, these proposals lacked the structural protections, institutional neutrality, and identity-parity mechanisms required to secure broad support. The current model learns from those limitations by grounding Athlone’s role in constitutional function rather than political aspiration.

Geographic and Structural Suitability

Athlone’s location at the geographic centre of the island provides several advantages:

-

It lies equidistant from major regional cities, avoiding symbolic centralisation.

-

It sits on the primary east–west and north–south corridors, ensuring island-wide accessibility.

-

Its historical neutrality ensures that no community can claim Athlone as part of its political heritage, making it ideal for hosting shared functions.

Athlone’s position on the River Shannon — historically a natural midpoint — reinforces its suitability as a civic location where shared administration can develop without implying absorption into either existing jurisdiction.

Modern Civic Capacity and Planning Foundations

Athlone’s existing and planned civic infrastructure strengthens its role within the Administrative Province:

-

Its designation under Project Ireland 2040 as a Regional Growth Centre supports the development of administrative, economic, and transport infrastructure.

-

It hosts significant educational, commercial, and military institutions, providing organic operational capacity.

-

Its modern planning frameworks identify it as a future “Midlands Green City”, capable of hosting high-quality civic and governmental facilities.

These attributes ensure that Athlone is not being artificially elevated into an administrative role; instead, its existing capacity is being aligned with the needs of a shared future governance system.

Function of Athlone Within the Administrative Province

Under the New Constitutional System, Athlone serves as:

-

the civic heart of the Administrative Province,

-

the primary location for shared operational functions,

-

the neutral centre through which administrative coordination is routed.

Its role is not to replace existing capitals, but to provide a balanced midpoint infrastructure through which shared governance mechanisms can develop. By functioning within the Administrative Province, Athlone avoids reinforcing the historical North–South binary and instead supports a re-centred island architecture where administrative authority is neither Northern nor Southern.

Preparing the Ground for the Next Stage

With Athlone positioned as the civic centre of the Administrative Province, the system is now ready to introduce the next component: the institutions required to coordinate policy, legislation, and cooperation across the island.

This sets the foundation for the forthcoming proposal:

5. Proposal: The Council of Ireland — Shared Governance Linking Athlone, Dublin, and Belfast.

5. Proposal: The Council of Ireland — Shared Governance Linking Athlone, Dublin, and Belfast

With the Administrative Province established and Athlone identified as the neutral civic centre, the next stage introduces the Council of Ireland — the institution through which structured cooperation, joint policy-making, and coordinated governance across the island can occur.

The Council of Ireland is not new. It is the latest development in a century-long constitutional principle:

that North–South cooperation requires a permanent institutional home, not informal arrangements or political goodwill.

This proposal sets out how the Council operates, how its authority is structured, and how it links Athlone, Dublin, and Belfast without subordinating any of them.

Purpose and Function of the Council of Ireland

The Council of Ireland serves as the central coordinating institution for shared governance. It does not replace Stormont or Leinster House, nor does it dilute their powers. Instead, it provides:

-

a structured forum for joint decision-making

-

a mechanism for coordinating policies across the island

-

a venue for addressing cross-border challenges

-

a constitutional bridge linking the two jurisdictions with the new administrative centre

Its function is operational, procedural, and constitutional — not symbolic.

The Council ensures that cooperation is:

-

predictable,

-

law-based,

-

insulated from political cycles, and

-

protected against unilateral withdrawal.

Institutional Architecture

The Council of Ireland is built around three civic anchors, each playing a defined constitutional role.

1. Athlone — The Administrative Centre (Neutral Hub)

Athlone hosts the Council’s:

-

permanent secretariat

-

treaty-implementation offices

-

policy-coordination units

-

intergovernmental working groups

Athlone’s function is to provide continuity, neutrality, and procedural transparency, ensuring that shared governance operates above regional or identity alignment.

2. Dublin — Legislative and Executive Interface (South)

The Council maintains formal links to:

-

Leinster House

-

Southern departments

-

regulatory and oversight bodies

These channels ensure Southern legislation, policy, and services are coordinated where required, while retaining full autonomy.

3. Belfast — Legislative and Executive Interface (North)

The Council maintains parallel links to:

-

Stormont

-

Northern departments

-

Northern regulatory bodies

These interfaces allow Northern law and policy to be aligned where appropriate, without being overridden or absorbed.

Together, these three centres create a tri-point governance structure that prevents institutional dominance by any single capital.

Core Competencies and Mandate

The Council of Ireland exercises defined and limited functions in areas where cooperation is essential.

1. Policy Coordination

The Council formalises cooperation in areas where:

-

cross-border services already exist

-

divergence risks operational disruption

-

integrated frameworks improve outcomes

2. Joint Programmes and Bodies

Existing all-island cooperation structures are re-anchored within the Council, gaining:

-

clear mandates

-

regular oversight

-

shared reporting

-

joint accountability

3. Oversight and Compliance

The Council monitors:

-

implementation of joint programmes

-

adherence to shared frameworks

-

operational efficiency

4. Dispute-Resolution Mechanism

A formal process is established to resolve Northern–Southern administrative disputes without political escalation.

5. Implementation of Shared Agreements

The Council ensures consistent execution of:

-

cross-border operational frameworks

-

aligned regulatory standards

-

cooperative protocols under treaty law

This prevents stagnation, duplication, and policy drift.

How the Council Operates (Practical Mechanisms)

The Council functions through:

-

Joint Committees

-

Standing Working Groups

-

Bilateral Liaison Offices

-

Treaty-implementation units

-

rotational chairing arrangements

Decision-making proceeds by consensus, ensuring no tradition or government exercises unilateral authority.

Transparency is maintained through:

-

recorded deliberations

-

published minutes

-

public reporting of decisions and work programmes

Why the Council Belongs in the Administrative Province

Locating the Council in Athlone:

-

removes symbolic dominance associated with Dublin

-

avoids political sensitivities tied to Belfast

-

ensures equal geographical and institutional accessibility

-

grounds cooperation in a neutral, nationally recognised province

This aligns with the model’s central principle:

shared authority must exist in a space belonging to everyone, and claimed by no one.

Integration Without Absorption

The Council does not:

-

override Stormont

-

subordinate Leinster House

-

merge the two systems

Instead, it ensures:

-

procedural clarity

-

institutional predictability

-

coordinated implementation

-

joint oversight without hierarchy

This embeds cooperation as structured, not improvised — balanced, not majoritarian.

A Foundation for the Next Stage: From Coordination to Constitutional Function

With the Council of Ireland now linking:

-

Athlone (the Administrative Province),

-

Dublin (Southern governance), and

-

Belfast (Northern governance),

the constitutional system gains:

-

a neutral coordinating centre,

-

legal pathways for intergovernmental cooperation,

-

reliable mechanisms for joint programmes, and

-

a safeguard against dominance by either capital.

With the Council of Ireland now established as the tri-point mechanism linking Athlone, Dublin, and Belfast, the institutional architecture for structured cooperation is complete. The system now has a neutral administrative centre, clear channels of coordination, and defined interfaces between both jurisdictions.

The next stage advances from coordination to constitutional function, by establishing how regional authority connects to the shared system through operational governance centres in Dublin and Belfast.

This leads directly to:

6. Proposal: Dublin and Belfast Governance Interfaces — Linking Regional Authority to the Shared System.

6. Proposal: Dublin and Belfast Governance Interfaces — Linking Regional Authority to the Shared System

With the Council of Ireland established as the coordinating body linking the Administrative Province (Athlone), Northern institutions (Belfast), and Southern institutions (Dublin), the next step is to define the operational infrastructure required to support this system.

This proposal introduces the North Administrative Building and the South Administrative Building — two parallel institutions designed to ensure that shared governance operates smoothly, transparently, and without regional dominance.

These buildings are not symbolic centres of power.

They are functional administrative engines that allow Stormont and Leinster House to interface consistently with the Council of Ireland and the broader governance framework.

They provide a structured way for both jurisdictions to participate in shared governance without losing autonomy or merging institutional authority.

Purpose of the North and South Administrative Buildings

The two buildings serve as operational bridges between:

-

Stormont and the shared governance system

-

Leinster House and the shared governance system

-

Athlone and both existing jurisdictions

Their purpose is to ensure that:

-

policy coordination is continuous,

-

administrative responsibilities are clearly assigned, and

-

shared decisions are implemented consistently across both regions.

They anchor the system in practical governance, not abstract cooperation.

1. The North Administrative Building (Belfast)

The North Administrative Building functions as the formal liaison centre between Stormont and the island-wide governance architecture.

Core Responsibilities:

-

Acts as the Northern interface for the Council of Ireland

-

Transmits Northern legislation, policy updates, and regulatory information to Athlone

-

Coordinates cross-border programmes in areas such as health, environment, transport, and education

-

Provides a stable administrative home for Northern staff participating in joint committees

-

Ensures Northern decision-making remains visible and protected within the shared system

The building enables Stormont to maintain full authority over its internal affairs while still operating within structured channels of cooperation.

It guarantees that Northern governance is never bypassed and remains an active participant in all shared processes.

2. The South Administrative Building (Dublin)

The South Administrative Building mirrors the Northern structure and ensures that Leinster House remains fully integrated into the shared administrative framework.

Core Responsibilities:

-

Acts as the Southern interface with Athlone and the Council of Ireland

-

Coordinates Southern policies and legislation intended for shared programmes

-

Harmonises Southern administrative functions with island-wide initiatives

-

Provides a central hub for South-based civil servants working on joint projects

-

Ensures Southern governance remains distinct, continuous, and respected within the new system

The building reinforces that Southern autonomy is not diluted, while maintaining clear pathways for structured cooperation.

Why Two Buildings Are Necessary

Having parallel North and South administrative structures ensures:

-

Institutional parity between both jurisdictions

-

A clear balance of authority

-

No single capital becomes dominant

-

Administrative neutrality is maintained

-

Implementation is synchronised but not centralised

This design directly addresses one of the core challenges of Irish constitutional design:

how to share governance without creating the perception of takeover by one region.

The two buildings provide practical reassurance that neither Dublin nor Belfast becomes the default centre of shared authority.

Integration With the Administrative Province

With Athlone functioning as the neutral administrative centre, the North and South Administrative Buildings serve as:

-

Regional anchors

-

Administrative gateways

-

Operational mirrors

-

Implementation centres

Together, these three nodes — Athlone, Belfast, and Dublin — form a triangular administrative architecture:

-

Athlone = Island-wide administration

-

Belfast = Northern administration

-

Dublin = Southern administration

This model preserves regional autonomy while enabling structured, island-wide coordination.

Operational Mechanisms

Both Administrative Buildings operate through:

-

Dedicated liaison offices connecting to Athlone

-

Joint policy teams assigned to cross-border programmes

-

Rotational co-chairing of committees to protect parity

-

Shared procedural guidelines aligned with the Council of Ireland

-

Annual reporting requirements ensuring transparency

-

Administrative oversight mechanisms to maintain efficiency

Their role is not to legislate or govern, but to ensure that governance decisions are implemented consistently, fairly, and without dominance.

A Foundation for the Next Stage

With the North and South Administrative Buildings established as the operational pillars of intergovernmental coordination,

the system is now ready for the next structural component:

7. Proposal: The Shared Judiciary — A Constitutional Court and Integrated Judicial Framework.

7. Proposal: The Shared Judiciary — A Constitutional Court and Integrated Judicial Framework

The next structural pillar is the shared judicial architecture that ensures lawful transition, constitutional balance, and equal access to justice across the island.

A stable constitutional system requires not only political cooperation, but an independent, island-wide judiciary capable of interpreting shared agreements, resolving disputes, and safeguarding rights.

This proposal establishes a tiered judicial structure that respects the autonomy of both existing legal systems while creating a single, neutral constitutional authority at the top.

1. Preserving Regional Legal Autonomy

Both jurisdictions retain their existing courts:

-

Northern courts, operating within their established common-law system

-

Southern courts, operating within their constitutional and statutory framework

These courts continue to handle:

-

civil matters

-

criminal law

-

family proceedings

-

commercial and administrative cases

-

regional appeals

This ensures continuity, predictability, and no disruption to either community’s legal expectations.

Key principle:

Regional courts remain fully operational — nothing is absorbed, overridden, or replaced.

2. Shared Appeals Mechanism

A new Island-Wide Court of Appeal provides a structured pathway for cases that:

-

involve cross-border issues,

-

raise shared constitutional questions, or

-

require harmonisation for all-island agreements.

It does not replace the existing appeal systems; rather, it sits above them, providing:

-

legal consistency,

-

procedural clarity, and

-

balanced interpretation of joint frameworks.

This level is essential for coordinating two legal systems without erasing either tradition.

Key phrase:

A shared appeals tier ensures alignment without centralisation.

3. The Federal Supreme Court of Ireland (Constitutional Court)

— The Neutral Guardian of the Shared Constitution

At the top of the system sits the Federal Supreme Court of Ireland, formally designated as the Constitutional Court of Ireland — located within the Administrative Province.

This is the highest judicial authority, responsible for:

-

constitutional interpretation,

-

intergovernmental disputes,

-

questions of competence between institutions,

-

rights-based claims, and

-

oversight of the Council of Ireland’s legal frameworks.

Its role is to ensure:

-

neutrality,

-

legal balance,

-

uniform interpretation, and

-

protection of Parity of Esteem in all constitutional matters.

It is designed as:

-

non-partisan,

-

geographically neutral,

-

independent of both legacy states,

-

accessible to both communities, and

-

constitutionally insulated from political pressure.

Key phrases (highlighted):

-

Federal Supreme Court of Ireland

-

Constitutional Court of Ireland

-

neutral constitutional authority

-

guardian of shared sovereignty

-

protector of Parity of Esteem

This is the first institution that fully expresses the evolved constitutional structure.

4. Judicial Appointments and Safeguards

To prevent dominance, the appointment process is built around structural neutrality:

-

Equal nomination rights

-

Cross-community confirmation

-

Fixed, non-renewable terms

-

Transparent selection criteria

-

Professional, not political, oversight

Appointments require cross-tradition consent, ensuring:

-

no single bloc controls the judiciary,

-

no tradition is under-represented,

-

and trust is maintained in both communities.

Key phrase:

The judiciary must be beyond political reach.

5. Jurisdiction and Legal Competence

The shared judiciary operates on the principle of:

-

dual autonomy (preserving separate legal systems), and

-

shared constitutional oversight (harmonising only where needed).

Its jurisdiction includes:

-

disputes involving the Council of Ireland

-

conflicts between regional laws and shared frameworks

-

rights protections embedded in the system

-

cross-border criminal and civil cooperation mechanisms

-

questions of legal interpretation arising from the Administrative Province

It does not:

-

rewrite regional legal codes,

-

interfere in devolved matters,

-

or impose uniformity.

Key phrase:

Authority is harmonised, not homogenised.

6. Role of the Judiciary in Safeguarding Transition

The judiciary is central to ensuring that the transition to the new structure is:

-

legal,

-

predictable,

-

balanced, and

-

protected from political volatility.

It acts as the constitutional referee, preventing:

-

overreach by any institution

-

erosion of identity rights

-

disruption to public services

-

unlawful interpretation of agreed frameworks

Key phrase:

Judicial independence guarantees constitutional stability.

7. A Foundation for the Next Stage

With the shared judiciary — including the Federal Supreme Court of Ireland (Constitutional Court) — established, the system now has:

-

legal continuity,

-

a neutral constitutional referee,

-

balanced appellate structures, and

-

a clear hierarchy of interpretation.

This prepares the ground for the final structural proposal:

8. Ensuring Balance in Constitutional Change — A Choice Between Three Futures.

8. Ensuring Balance in Constitutional Change: A Choice Between Three Futures

The transition to a federal model must be guided by consent, balance, and a clear rejection of triumphalism. Any constitutional change perceived as a victory for one tradition over another risks deepening division rather than healing it. This model embeds Parity of Esteem at every level — ensuring that no identity is erased, no tradition dominates, and no community is left behind or made vulnerable.

It offers more than just a new system — it provides a lawful, structured alternative to gridlock. In this model, neutrality in governance becomes a bridge between traditions, not a symbol of avoidance. If change comes, it must come through consent — not conquest, with safeguards that honour heritage, rather than erase it.

This is a choice between three futures:

Option 1: Remaining in the Status Quo (Partition):

-

Maintains existing structures with no new guarantees of fairness.

-

Risks deepening mistrust and societal division.

-

Reinforces the idea that progress can be indefinitely delayed or denied.

-

Sustains a fragile balance without structural reform.

-

Prolongs uncertainty through a seven-year waiting period after a failed border poll — delaying reform and fostering public anxiety in the lead-up to another referendum.

-

Leaves both traditions trapped in a reactive cycle, where politics is shaped not by vision or progress, but by demographic pressure, electoral fear, and the erosion of trust in the possibility of meaningful constitutional change.

Option 2: Traditional Unification (Absorption):

-

In all its forms — whether full absorption or a devolved model under Dublin — this option still results in sovereignty transferring entirely to the existing Republic of Ireland, without shared institutions, without constitutional parity, and without a balanced framework for identity protection.

-

Imposes constitutional change without institutional safeguards.

-

Risks alienating communities and destabilising governance.

-

Lacks formal mechanisms for Parity of Esteem and shared sovereignty.

-

Symbolises unity — but risks undermining it through exclusion.

-

Risks triumphalism if a border poll is won — potentially reigniting division, destabilising peace, and increasing the risk of renewed unrest.

Option 3: A New Federal Ireland (A Shared Future):

-

Ends political dominance.

-

Guarantees equal representation.

-

Preserves cultural identities.

-

Embeds Parity of Esteem in governance.

-

Offers a fresh constitutional beginning for all.

-

Builds unity among people, not through uniformity, but through structured balance.

-

Because this approach defines reconciliation through enforceable structure rather than intention, it exposes the structural weaknesses of the other options when placed side by side.

Because this approach defines reconciliation through enforceable structure rather than intention, it exposes the structural weaknesses of the other options when placed side by side:

-

The first option defers reform and locks communities into recurring constitutional uncertainty every seven years.

-

The second option chases the unfulfilled promise of 1916 — but lacks the safeguards to secure lasting peace.

-

The third option offers reconciliation through structure, a shared future, and the foundations for permanent stability.

Crucially, the principles underpinning this third path are not new or radical. They have already been jointly accepted by both the Irish and British governments through the Good Friday Agreement, which enshrines consent, parity of esteem, non-domination, and shared responsibility as the basis for constitutional legitimacy.

The Parity Accord does not introduce a new premise — it completes the logic those governments already endorsed, by giving those principles durable constitutional form.

This is therefore more than a political choice. It is a generational decision between:

-

inclusion or inertia,

-

structure or instability,

-

a shared future or repeated fracture.

Do we build the future — or repeat the past?

What follows is the roadmap for that future.

The federal model outlined in this White Paper is the only option that offers:

-

stability without domination,

-

reform without erasure,

-

peace without triumphalism.